Enter the drone

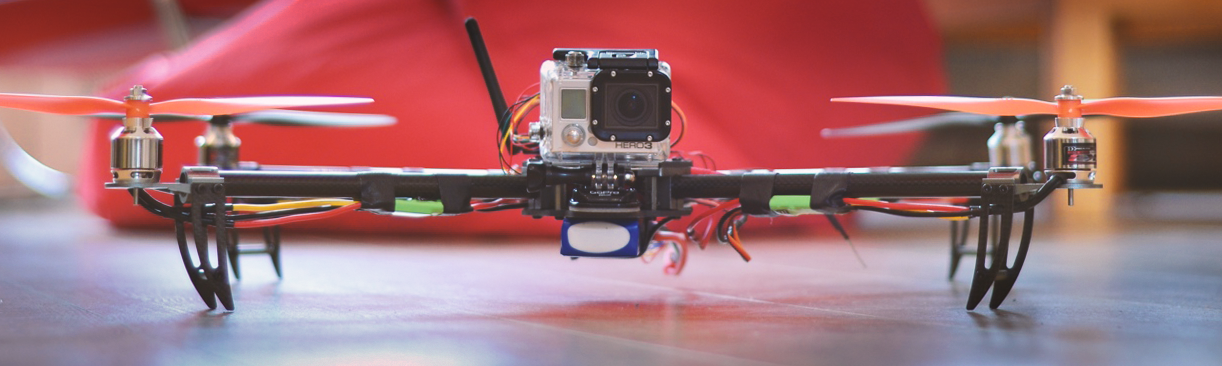

As it is becoming a tradition on this blog, let’s do a quick dive into a personal story. Back in 2010, part of my job was to explore new technologies and hack them to find applications that are not necessarily obvious. When I saw a drone fly for the first time at the Dutch Game Garden office where I worked (I mean a small civilian quadcopter, not the military stuff), I was mesmerized… There is something so weird about the way they fly; it seems impossible. I wanted one, and I needed to learn more about it.

My first thought was that the damned things were too expensive, and I was probably going to break it in no time. So, cue brilliant idea: I went on to spend twice the money and hundreds of work hours designing and building my own fully custom quadcopter. And it was totally worth it in every way possible.

A few things came out of it: I learned a lot about many different fields: precision 3D design and printing, laser cutting, materials, aerodynamics, motors, controllers. I almost burnt my house down, I gathered a super-cool group of art students to create intensive seminars on “The artistic potential of aerial robotics”, and I learned about a relatively simple, and magic, algorithm that allows something with an impossibly unstable design to actually fly in a controlled way.

So what does a drone, an airco unit, and political ideology have in common?

Keeping a drone in the air, keeping temperature stable, riding a Segway or a OneWheel, fighting racism and inequality, and designing legislation and regulations are all very complicated, seemingly impossible balancing acts in situations where a lot of external “forces” keep shifting and trying to throw everything into chaos.

Whether we’re trying to stop war or gender abuse, racial discrimination, designing immigration policies, optimizing economy and industry growth while controlling pollution and ecological impact, we’re essentially performing balancing adjustments. Even if we don’t realize it or disregard it to simplify things, all the activities we do on any of the sides can likely be overdone catastrophically.

That’s what I want to talk about, balance and how the techniques machines use to achieve it can be really enlightening. Now, before disregarding this as boring and unfashionable centrist propaganda, bear with me for a few minutes. I will not make any point towards left, right, or center. I will try really hard to just focus on the decision-making processes and fighting emotional bias.

How machines do it

The main algorithm behind so many amazing self-balancing inventions is called a “PID controller” (Proportional-Integral-Derivative). It’s a loop that continuously calculates the error between where we are and where we want to be, then applies corrections based on three pieces of information:

- The current error (Proportional): the further we are from where we want to be, the harder we should push.

- The accumulated error over time (Integral): if we’ve been off target for a while (our efforts are not working), we need to push harder.

- The rate of change (Derivative): This component predicts the future; if we’re moving fast towards the target, we should ease off or even push back to avoid overshooting.

When balancing, these three components need to be re-calculated over and over again as fast and as often as possible. The more unstable the system, the faster we need to do these calculations. Even though PID controllers have been around since the 1920s (first introduced in production by Nicolas Minorsky for automated ship steering), small quadcopter drones as we know them today were not stable enough till the mid-2000s because there were no computers that were light enough and fast enough to control (and be carried by) something that small and unstable.

Tuning

PID controllers can balance anything, but for each specific task, they need to be tuned. Tuning a PID controller is critical for its performance; this consists of deciding how much “importance” to give to each component. In the following image, you can see what a process of tuning looks like. The blue line can be seen as the “position over time” of an object that starts at 0 and is trying to balance on the red dotted line. In the animation, you see the Kp, Ki, and Kd values being adjusted; they set how “important” each component is:

How humans do it

When we look at how society reacts to social issues, we often see a strong focus on the “P” (Proportional) component - we see a problem and push hard to fix it. This is natural and important - if there’s discrimination or inequality, we should absolutely work to correct it. If there are ways to improve productivity, innovation, and the economic situation, we should definitely chase that.

The “I” (Integral) component is also seen often - when people feel their concerns have been ignored for too long, the pressure for change builds up. This accumulated frustration often leads to stronger pushes for reform. This really helps to fix conditions where we are stuck by some “external force” pushing away from the target. But it also increases the chances and the magnitude of overshooting out target.

However, the problem is when the Integral “I” does its job and unlocks change, the “D” (Derivative) component becomes really hard to implement. It’s extremely hard and counter-intuitive to hit the brakes after so much fighting, exactly when the change you wanted finally starts happening. But without this component, we risk overshooting our targets, potentially creating new forms of inequality or discrimination in our attempt to correct existing ones. Or triggering a strong pushback from people that are more focused on the other side of an issue, which pushes us right back to where we were in the beginning, but with more animosity and division between groups of people and therefore a more unstable system. (you can see this happening on the graph when the Ki grows and the Kd is at 0 the overshooting intensifies) The D component calms things down and makes us reach our target faster.

This overshooting isn’t just theoretical. History shows us numerous examples where revolutionary movements, while addressing real injustices, went too far in the opposite direction, creating new forms of oppression. The French Revolution’s Reign of Terror, various communist revolutions, and even some modern social movements have shown how the lack of a “D” component and that can lead to outcomes that nobody wanted.

This isn’t an argument for moving slowly - remember, PID controllers in drones make thousands of adjustments per second and create incredibly nimble aerial robots. Rather, it’s an argument for moving thoughtfully, with awareness of not just where we are and where we want to be, but how fast we’re moving and what new dynamics our actions might create that might further destabilize us.

The challenge, of course, is that social systems are far more complex than drones or air conditioners. Let’s think about why.

The balance point is incredibly fuzzy

There is not really a uniform concept of a perfect society we all want to live in. There are as many target points as there are people. So we don’t even know what we are aiming for exactly. There is a large variety of cultures, preferences, geographic locations, and economic backgrounds that affect where people set their ideological goals. Also, we’re chasing multiple targets at once, that often influence each other. This means we’re aiming at a range instead of a point, which makes it very hard to figure out when to push and when to ease down to avoid overcompensation.

There is not only one controller, there are many

Every person or small group of people acts as a small PID controller on the system, with a different target balance point, reacting and causing feedback with others, often with system externalities like emotions, animosity, or hate affecting decision-making rather than a specific societal goal. So bias comes once again into play in this blog. The target point of each person is normally biased against the ones pushing on the other side. And since people’s lives are literally at stake, it’s very easy to fall for hate. Which brings even more bias and all measurements go down the drain.

It just takes so damn long

It takes more than a generation to correct a societal shift, making it challenging to educate children to continue and adapt (and sometimes reverse) the approaches that their parents and grandparents adhered to. This generational lag means that the values, beliefs, and biases of one generation can deeply influence the next in a way that might no longer be relevant. As a result, societal change can be slow and arduous, with each generation inheriting the unresolved issues and partial solutions of the previous one. This continuity can perpetuate cycles of behavior and thought patterns that are resistant to change (we keep swinging back and forth), making the process of achieving a balanced society even more complex and prolonged.

So what do I propose here?

With this, I want in no way to give you my personal opinion on what’s right or wrong ideologically (what the balance point should be), you set your red dotted line where you think humanity should go. All I want is to raise a different perspective on taking actions that I learned from engineering. And try to explain upfront that if somewhere, somehow, we end up in an ideological discussion, my pushing back on a point might not mean that I disagree with what you think is right or wrong, it might just be that I think it’s time to get the “D” tuned up a bit. So please don’t hate me 😊

Once again, if you got this far, I am so thankful to you for coming back and reading my rants. I hope it was at least entertaining and gave you something to think about. Please subscribe, and get in touch with me to discuss further, give me feedback, or just a kind word.

Cheers!